Strategic considerations for real estate investment: comparison with other secure investments

by Peter Fassl & Helmut Seitz

a) As the analysis in Part 1 demonstrated, the perceived scarcity of land, whether for development or cultivation purposes, combined with steadily growing inflation, necessarily leads to a rethinking of how one might strategically invest in real estate. As shown, the typical real estate investor thrives on acquiring land, building on it, and then reselling it, all in the hope that his profit from this cycle will not be completely eroded by the price of a replacement purchase having risen more than the profit he has made. However, the ultimate goal is always to secure the basic raw material of land for future value creation. This does not necessarily mean becoming the owner of the land. It is quite suffcient to be use it in the same way as the owner. This instrument is called a “building lease” in the DACH-region and a “long lease” in many other jurisdictions.

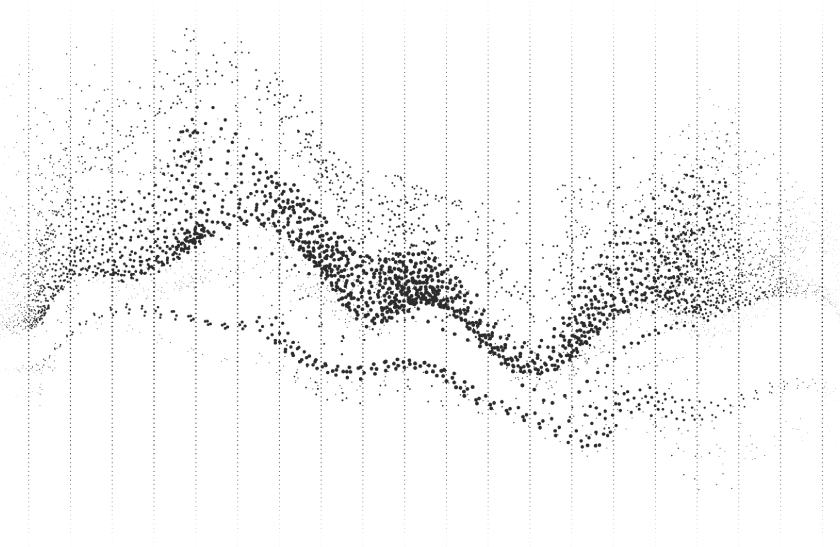

b) If we separate the investors horizontally, i.e., the owner of the land is not the owner of the building, and presumably a third person rents the property, the first question is: who has what expectations regarding their investment? The owner of the land undoubtedly has the most sustainable value and the least work in adding value. He will therefore be satisfied with the lowest return compared to the other parties involved. Now, how can such an expectation of return be brought to a comparative calculus? In my opinion, land that generates a return, independent of any investment in buildings, tenant interests, etc., can be most easily compared with an investment in government bonds. If we calculate a simple matrix (see chart), there are four differences that distinguish these two forms of investment; namely 1) liquidity, 2) risk, 3.a) inflation hedging of the return, 3.b) inflation hedging of value. Round 1 clearly goes to the government bond, as these have a stock market price and can be traded daily. When it comes to risk, the question of which is safer is not so easy to answer. If sovereign risks in the DACH region hopefully can be considered as low at the time this article goes to print, that is no longer the case for more eastern parts of Europe. Regardless, it can be assumed that, at the end of the day, land still carries a higher risk, even if only slightly, than a government bond in the same area. Round 2, on the other hand, clearly goes to long lease property. In the case of a building lease, an annual inflation compensation is typically agreed upon, and in addition, the value of the property naturally increases at least in line with general inflation.

Whereas government bonds usually have a fixed interest rate over the entire period and the nominal value acquired is only devalued by inflation and never revalued. Let us now evaluate these premiums and discounts in a comparison of the two investment instruments: liquidity -0.5% to the detriment of the long lease, risk -0.25% to the detriment of the long lease, inflation (3.a and 3.b) 0.5% each in favour of the long lease property. The result is an advantage of the long lease property by 0.25%; i.e., if one compares the government bond with the land that earns a building lease interest, the latter would have to be satisfied with a quarter of a percent less in return. If we take today's 60-year government bonds in the DACH region, they all pay barely 1.5% per annum. So, an investor would have to be content with a profit margin of 1.25% to have the same overall effect if he acquired purely land.

c) Whether a real estate developer is confronted with a land owner as a partner who only expects a 1.1% return, or one who is “greedy” and wants to earn perhaps 3%, is, strictly speaking, irrelevant. Since in any case, the right of use and thus the chance of profit always "costs" the developer less than if he took out a loan from the bank. After all, even with a 25-year interest-free term, a loan would burden the cash flow with 4% of the value.

A financial mathematical comparative calculus thus clearly shows that a vertical division and a breaking of the typical real estate cycle would be suitable to open up sustainable market opportunities depending on the respective input of time, performance and money. In part III, we will show you in greater detail how this can be done.

Photo: ah_fotobox - stock.adobe.com

/https://storage.googleapis.com/ggi-backend-prod/public/media/3539/real-estate-investment-a71710450.jpg)

/https://storage.googleapis.com/ggi-backend-prod/public/media/5771/HSP-Rechtsanwaelte-GmbH_Logo-2024.jpg)

/https://storage.googleapis.com/ggi-backend-prod/public/media/6063/Real-Estate-Kapp-cropped.jpg)

/https://storage.googleapis.com/ggi-backend-prod/public/media/6317/PIXABAY-house-1867187_1920-cropped.jpg)

/https://storage.googleapis.com/ggi-backend-prod/public/media/6061/Real-Estate-article-cropped.jpg)

/https://storage.googleapis.com/ggi-backend-prod/public/media/6060/Real-Estate_Saghi-Khalili-cropped.jpg)